by Hilary Kiely

Traditionally, if you were to get married in Ireland, you would not or even could not do so during Lent. The Christian calendar marks this period leading up to Easter off as a time for reflection and penitence. Since around 325 A.D., after the Council of Nicea, Christians have observed varying levels of privation running a gamut from 40 days of fasting to giving up sweets. This practice would already have been part of Christian observance when St Patrick came to Christianise Ireland sometime around 432 A.D. (Ironically, many use the feast day of St Patrick on the 17th of March to take a day off from Lenten observations.)

The beginning of the Lenten season is marked by Ash Wednesday, which is historically a strict fast day (in early and Medieval Christianity no food at all, later no full meals or no meat may meet the requirements) to set the tone for the next 40 days of austerity. Ash Wednesday is preceded, however, by Shrove Tuesday, known in Ireland as Pancake Tuesday, which is a chance to celebrate and indulge a little because traditionally things like meat, dairy and eggs have to be used up before the fasting begins. This also meant that weddings could only take place up until Shrove Tuesday. Traditionally, Shrovetide, then, was a very active time for marriages and matchmaking.

All the single ladies (and gents)

And if you were of marriageable age but still single on Ash Wednesday?

Well, there were local traditions across the island of Ireland for marking your status. In Waterford City, for example, you might have been expected to sit on a log (or get tied to it) and be dragged through the town centre. In the wider county, they settled for painting crude signs on the whitewashed walls of a bachelor’s house with tar. And in Donegal, a bachelor might be given a wife – one made of straw and dressed up in cast-off women’s clothes and placed in front of the house. Those might be embarrassing, but a good deal dryer than getting ducked in a pond, as in County Cork. (Ó Danachair, p 100)

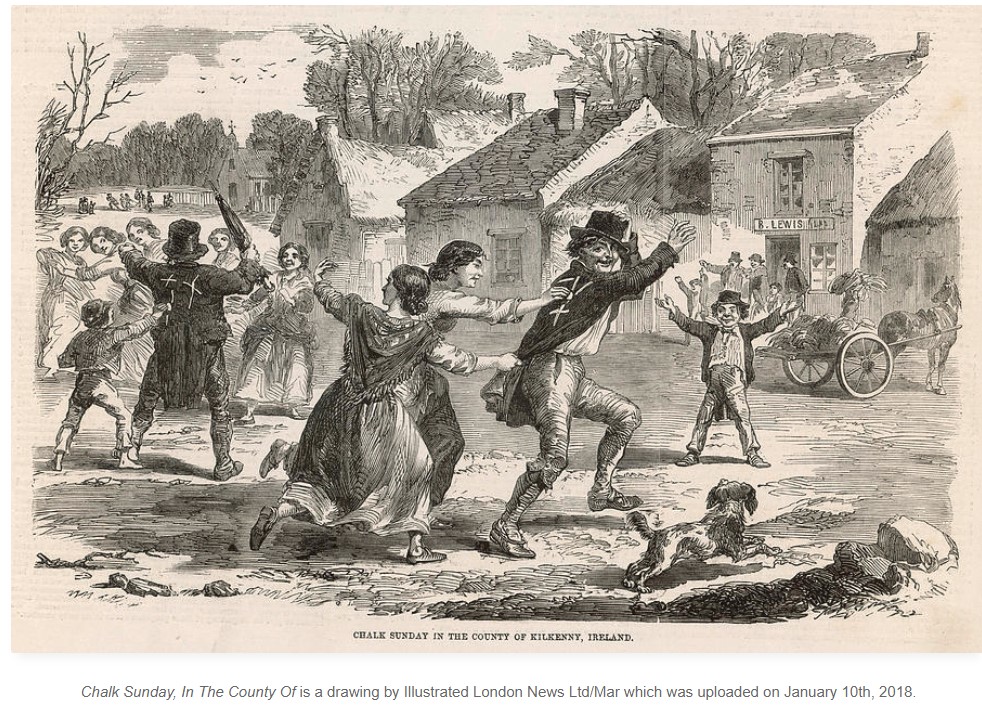

Chalk Sunday

In other parts of the country, the first Sunday in Lent was known as Chalk Sunday. On this day, singletons in Tipperary, Clare, Mayo, Sligo, Kerry, and Galway would be marked with chalk on their way home from Mass.

In Tipperary it seems that the chalking was reserved for older men who in their 50s and above who were chalked and it was young lads who did the chalking, according to a number of account in the School’s Collection of the National Folklore Collection (NFC:TSC). In Clare, everyone at any age was fair game for being the chalker or the chalkee:

“It is the Sunday after Shrove Tuesday. Anybody who did not get married and who were of age to get married are chalked on that Sunday. Young and old enjoy chalking those people.” (Belvoir, Co Clare NFC:TSC, Volume 0586, Page 110)

It was told by an un-named 38 year old female informant in Kerry that “any boys or girls that were old enough to marry and did not got a good chalking on (Chalk Sunday). They were said to be “hanging on the dresser” for another year. John Goally can hang himself on the dresser this year and maybe next year. (NFC:TSC, Volume 0413, Page 153) Now, I don’t know who John Goally was, but our informant doesn’t seem to be pleased with his unmarried status.

Rather ominously, it was said in Eyrecourt, Co Galway that “No one escaped the Chalking”. (NFC:TSC, Vol 0056, pg 154).

Smuit or Puss Sunday

In some places, it wasn’t necessary to mark people, as they marked themselves, with a pout or a sulky and vexed expression at having to watch the newlyweds at Mass on Sunday. In some places the day was called Domnach na Smuit or Smut Sunday and in others, Puss Sunday. These come from the Middle Irish words smúit, which means smoke cloud (thus a stormy expression, perhaps) and pus (a pout or sulky expression)*.

Salt Monday

If you hadn’t been marked or married yet, you might find yourself salted instead. In Galway, Sligo and Mayo especially, unmarried people, especially young women would get salt thrown at them “to preserve the unmarried fresh and healthy until the following Shrovetide”. In Dunmore, Co Galway, they couldn’t wait until Monday, instead taking advantage of the market day on the first Thursday. In Tobercurry, Co Sligo, it was recalled that:

“The first (morning) Monday of Lent was called Salting Monday. On that day the children used to throw salt on all the unmarried women so that they would be preserved for the next year.” (NFC:TSC Volume 0171, Page 324)

In a few places in the midlands, such as Moate and Mullingar, rather than being marked with chalk, ashes were thrown at the victims, or bags of ashes pinned or tied to their clothing. ‘You will have the ashes thrown at you!” was apparently a warning to folks who seemed not to be trying hard enough to find a mate during Shrovetide. (O Danachair, p 100)

Where your own family came from, or live now, was your bachelor famer uncle or maiden aunt chalked, salted, or covered in ash?

*Visit the Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language http://www.dil.ie/ if you’re interested in the language.

References:

Ó Danachair, Caoimhin “Distribution Patterns in Irish Folk Tradition”, Béaloideas, Iml. 33 (1965), pp. 97-113

Salt reservoir photo from SALT-MAKING AND FOOD PRESERVATION Author(s): Muiris O’Sullivan and Liam Downey Source: Archaeology Ireland , Vol. 30, No. 4 (Winter 2016), pp. 21-25 Published by: Wordwell Ltd.