by Hilary Kiely

In Ireland there can be millennia and layers of meaning packed into a place name. The name can tell you about the landscape, the history, or local legends. It can sometimes be difficult to unpack those layers. Like family names, different spellings, anglicisations, and phonetic spellings can lead to confusion regarding the origins of the name before you even get to deciphering the actual meaning. Many placename elements are readily recognisable even without a working knowledge of the Irish language. Others will have gone through many iterations and you mightn’t be able to guess the original. But unravelling the origins can reveal interesting nuggets of information about your locality.

The primary school nearest me is known locally just by the name of the townland it’s located in, although its officially named for Saint Joseph. In Irish, the name is An Bhuaile Bheag. On a map, you may find Buaile Beg or Boleybeg or Booleybeg. What does that tell us about this place? Well, this was a “little booleying place”. And that is the beginning of finding out about the cultural landscape of this townland at the top of a hill that runs down to Galway Bay.

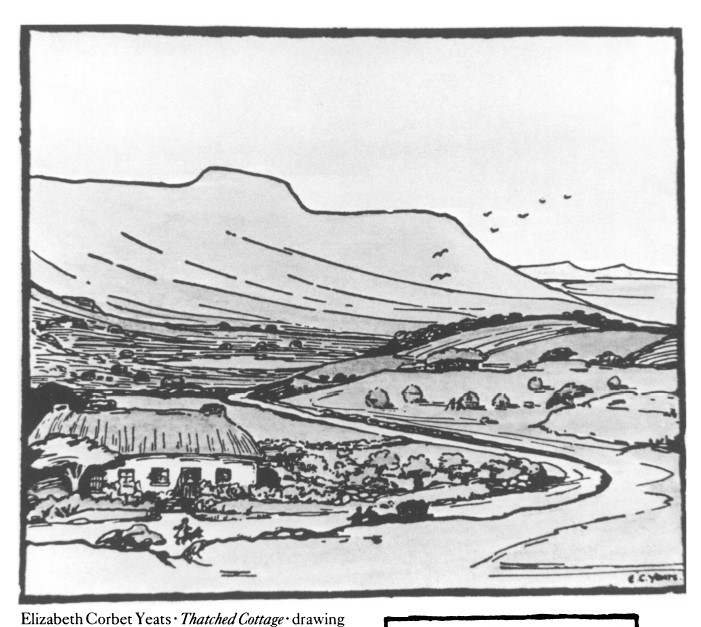

The school was established in 1891 but it was a place where young people would have gathered and learned long before that. Up until that around that time, booleying was an active agricultural practice in rural Ireland. A booley is a “dairy milking place of summer pasturage”. In summer, farmers would move their cattle away from their home places up to commonage areas in the uplands where the land was not fit for growing crops but had rough pasturage to support cattle grazing. Rough shelters were erected, and young people would stay in them during the summer months to keep an eye on the herd. Often the booleying places would not have been so far away that they couldn’t have been gotten to and from at the beginning and end of each day but, aside from the inconvenience of that, the dairy herd would need to be milked twice daily to maintain production and the continuous presence of people discouraged both robbers and predators. Or mostly.

According to some folktales, robbers were wont to attempt not only to abscond with cattle in echoes of ancient cattle raids but also with the young women who were minding them. One type in particular has the clever young woman staging her own rescue:

Robbers have come to the booley hut and are planning to take the young woman away with them. She is there with her younger siblings, a brother and a baby in the cradle. She has to calm the fussing baby and so soothes it with a lullaby.

‘Rise up Aodh and leave the booley,

Go to the homestead and raise a host

Say that a kidnapping is under way;

Four, five, a hound and a boy’

The robbers pay no heed to the woman’s singing but her brother, Aodh, gets a bucket and slips out, ostensibly to go for water. When out of sight of the booley, legs it for home. The farmers then mobilised and came to the rescue of the both the young woman and the cattle. (Ó Catháin, 114)

Booleying was important not alone because it allowed for the farmers to avoid having to give up arable land or hay making fields to the cows, it made for healthier cattle along coastal areas and allowed for peak milk and butter production. Even more than this, it was a way of mixing socially with other families, of cultural exchange, and something of a rite of passage.

“…it gave young people an appropriate space to act out a transitional time of life in a way that benefitted the community beyond basic labour considerations. Sending them to summer settlements to form temporary groups of practice was a rite of passage. Girls acquired cultural knowledge through music and they bolstered dairying, knitting, and spinning skills that sustained not only the booley settlements but eventually, as well, the social structure of home. The fact that their apprenticeship and socialization took place in landscapes that tenant families had to share, as commonage, is important too. Dwelling and working on common land would have instilled in people from an early age the value of mutual understanding and negotiation. (Costello 2017, p197)

Folklorist Kevin Danaher (Caoimhín Ó Danachair) recorded in his 1964 book Irish Customs and Belief that “…old people tell of the buaile as a very happy place, full of song and laughter. On Sunday evenings the girls from several buailes would come together and the young men came up from the farms to be with them, and there was music and dancing and gaiety on hillsides that now hear only the bleat of the sheep and the cry of the grouse and the curlew…”

There is a strand of folksong that records women reminiscing about their time minding the cattle. One such song is Na Gamhna Geala (The White Calves). One verse runs:

Ó, bheirim se mo mhallacht do tsagart a phós mé,

‘S an darna mallacht do na bailte móra.

Siadsan nár chleacht mé riamh i dtús m’óige,

Ach mé ag rinnce ins a’ tsamhradh ‘gus na gamhna liom a’ seoladh.

(My curse on the priest that married me,

And my second curse on the big towns.

That’s not how I spent my youth,

But dancing in the summer and herding cows.)

Interestingly, evidence of booleying is embedded in the landscape abundantly in place names, but sometimes the booley is confused with the Irish word baile (plural bailte as in the verse above), which means town and is quite a different sort of place altogether!

If your home place was in a farming area and there is a booley place name near enough to it, chances are good your forebears spent some time there during the summer, making butter by day and making music in the long evenings.

This article draws heavily on the work of Dr. Eugene Costello. For more, visit his article at RTÉ Brainstorm, refer to the works cited (below) or his book Transhumance and the Making of Irelands Uplands, 1550-1900. Also, be sure to visit logainm.ie for more buaile-related place names.

References and further reading:

- Costello, Eugene. (2017). “Liminal learning: Social practice in seasonal settlements of western Ireland”. Journal of Social Archaeology, Vol 17(2), pp 188-209

- Costello, Eugene (2016) “Seasonal Management of Cattle in the Booleying System: New Insights from Connemara Western Ireland” Cattle in Ancient and Modern Ireland. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp 67-74

- Danaher, Kevin, Irish Customs and Beliefs (Mercier Press 1964)

- Ó Catháin, Séamas, “The Robbers and the Captive Girl. Ancient Antecedents and Other Elements of a Rare Irish Legend Type” Béaloideas, 1994/1995, Sounds from the Supernatural: Papers Presented at the Nordic-Celtic Legend Symposium (1994/1995), Published by: An Cumann Le Béaloideas Éireann/Folklore of Ireland Society. pp. 109-146

I think I remember them referred to as The Boleys. This was in or near Monasteraden, Co. Sligo.

Indeed! Boley is definitely one of the spellings we see today for a place that used to be a buaile.

Is the meaning any different from what is meant by the term, shieling?

Hi John, these are closely related cultural practices. Taking livestock to summer pasturage would have been practiced across Europe from pre-historic times. “Shieling” comes to us from Old Norse (this term is used in Iceland as well as in Scotland) and “buaile” has an Old Irish root (some linguists think it may be ultimately derived from Latin: bovis = cow). Culturally shieling and booleying do seem quite similar, although the Irish practice seems quite particular to cows and shieling seems to encompass all grazing animals. I may have to see if I can find out if there have been any comparative studies done! You might also find this project of interest: https://www.theshielingproject.org/the-tradition-of-the-shieling/