by Hilary Kiely

In the lead up to the Easter Rising of 1916, Ireland had been riding a growing wave of cultural nationalism, demonstrated by the Gaelic or Celtic Revival. The Revival included literary, language, and political movements, but the visual and applied arts also participated in this Celtic Renaissance of the mid-19th into early 20th centuries. The visual language of early Medieval Irish illuminated manuscript became the visual language of the Irish Arts and Crafts Movement.

Handmade Revolution

Outside of Belfast, Ireland did not have an industrial revolution, a catalyst for other countries’ Arts and Crafts movements. In other places, the explosion of hand-crafts was in response to the mechanisation of labour. In Ireland, politicians, writers, artists and artisans alike were reacting against British colonialism.(1) The visual and applied arts looked to the pre-Norman period of artistic production, the Golden Age of the Isle of Saints and Scholars, to reawaken Ireland’s native traditions. As Douglas Hyde said, “Celtic Art is the best claim we have upon the world’s recognition of us as a separate nationality.”(2) Indeed the pervasive use of these styles allowed the manuscript folios to imprint themselves on the inner eye of even the most modern of artists. The influence can be seen in works by such artists as Mainie Jellett, the first Irish abstract artist to exhibit a cubist work in Ireland.

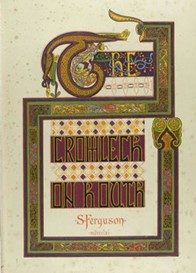

Because Ireland largely did not go through the same competition with machines for their livelihoods, the Irish Arts and Crafts movement was rooted in culture and identity. Naturally enough, then, it built on the antiquarian movement that gave rise to the contributions of such scholars as Margaret Stokes, whose body of work includes illustrations and photographs of Irish antiquities, as can be found in her 1887 book Early Christian Art in Ireland, which was reprinted regularly into the 20th century and “helped mould artistic perceptions of Irish heritage in the newly independent Ireland”.(3) Stokes also illustrated the poet Samuel Fergusson’s The Cromlech on Howth (1861), an elegy for the death of Oscar, son of Ossian and grandson of Finn MacCumhail of myth and legend, illuminating a cover page which could easily have been produced in an early Christian scriptorium.(4)

Around 1904, artist Hugh Lane said that Ireland’s greatest achievements in art predate the 12th century when cultural development was interrupted by the Norman invasion and the turmoil of the following centuries. The artists and artisans of the mid-19th to early 20th century period were picking up where things were left off in a very real sense. (5)

Cultural Nationalism

The Antiquarian movement, spurred on by the discovery of such Celtic relics as the Tara Brooch (unearthed in 1850), fed the revival and the design aesthetic of the Arts and Crafts artisans. These in turn spurred on cultural nationalism. The “cultural credentials” of the pre-Norman past provided a pedigree supporting the assertion of Irishness, of an identity separate from the invaders. If Empire assumed itself to be more civilised than the Irish, Ireland’s writers, artists, and artisans could stand on the shoulders of the poets, scribes and scholars who had inhabited the island in earlier centuries and produced the Books of Kells, Durrow, Leinster and Lecan, the Celtic High Crosses, the Tara Brooch and Ardagh Chalice. Despite perhaps seeming backward-looking, these design choices should instead be regarded as forward looking, one of many aspects in the Revivalist cultural arena, asserting the island’s rejection of colonial control.”(6)

Women a driving force of the Arts and Crafts Movement

Central to the Arts and Crafts movement in Ireland was the formation of guilds and collectives of artists and crafts people operating in many forms of craftsmanship from metalwork to weaving and embroidery to woodcarving to stained glass. Many of these guilds were formed by women. The movement brought about “a temporary reversal of long-standing assumptions about gender roles”.(7)

Lace workshops providing employment for young women during the post famine years provided an example for the schools of the arts and crafts branch of the Celtic Revival:

Sophia St. John Whitty’s Bray Woodcarvers (1887), Mrs. Montgomery’s Art Metalwork at Fivemiletown (1892), and Mrs. Vere O’Brien’s Limerick Lace School and Clare Embroidery; Lady Mayo also revived the Royal Irish School of Art Needlework. In a move to create more local focal points for various scattered cottage industries, an 1886 committee consisting of some of the landed ladies in Ireland was set up to ensure that Irish industries would be strongly represented at the Edinburgh International Exhibition that year, and after to establish a home arts and industries association, the Irish Industries Association. This was mainly focused on lace making, but some efforts to promote wood-carving were made, too. (8)

Wood carving was included through this association in the in ‘The Irish Village’ at the Chicago World Fair in 1893. Irish wood-carving had also been represented at the Edinburgh Exhibition by some pieces exhibited by a group call ed the Irish Association for Promoting the Training and Employment of Women, based in Kildare Street, Dublin, where scrivenry, plan-tracing, and illumination were also pursued. This same organisation produced the ‘Irishwomen’s Jubilee Offering to the Queen’ in the form of a large oak chest, carved with Celtic interlaced ornament, which contained an illuminated address bearing nearly one hundred and fifty thousand signatures. Records state that the chest was carved by some Irish ladies who pursued bog-oak carving as a recreation but they are not identified by name.

Dun Emer and An Túr Gloine

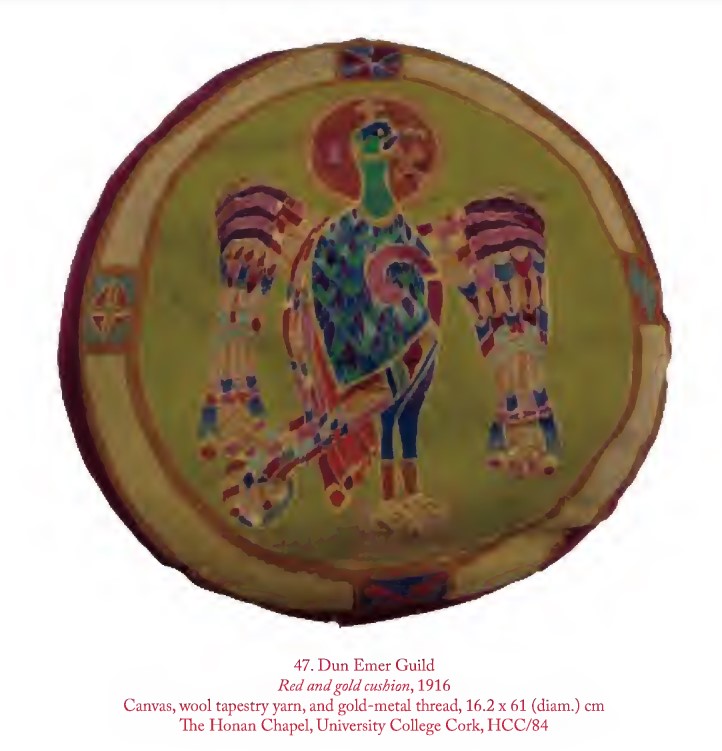

The Dun Emer Guild (the Fortress of Emer), formed by Evelyn Gleeson and Yeats sisters Lilly and Lolly, was named for the wife of mythological hero Cu Chualain, known in the mythology for her weaving and embroidery. This collective produced rugs and embroidery as well as books and prints. A snippet from the prospectus reads:

“A wish to find work for Irish hands in the making of beautiful things was the beginning of Dun Emer… this, of course, means materials honest and true & the application to them of deftness of hand, brightness of colour, and cleverness of design. Everything as far as possible, is Irish: the paper of the books, the linen of the embroidery and the wool of the tapestry and carpets. The designs are also of the spirit and tradition of the country”(9)

Eventually, the Yeats’ would branch off the printing arm to become Cuala Press in 1908, naming it for the pre-Norman name of the area of Dublin they operated in, leaving the textile arts to Dun Emer.

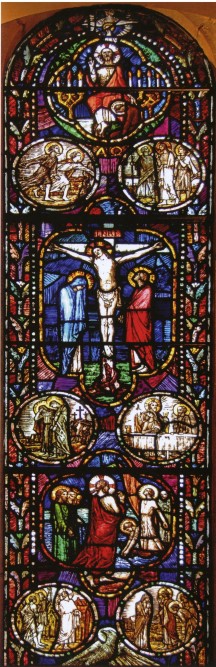

An Túr Gloine (the Tower of Glass), founded by Sarah Purser, was a stained glass collective which produced internationally regarded windows. It became the leading producer of stained glass in Ireland and their work can be found all over the island, and beyond as well. You can find a map of An Tur Gloine and Harry Clarke windows at Heritagemaps.ie.

The Honan Chapel

The recently refurbished Honan Chapel, or Saint Finbarr’s Collegiate Chapel is stands as a testament to the artistry of the Arts and Crafts movement in Ireland, showcasing some of its finest artisans. It was consecrated in November of 1916 and encapsulated much of the cultural nationalism of the time. The press around the reopening has mentioned a regrettable lack in the credit given to the women who were responsible for much of the beautiful craft that make the chapel so resplendent. Let’s give them a little credit here:

- The chapel itself was commissioned by a woman. Isabella Honan, scion of a wealthy butter merchant family, left a detailed bequest for this exquisite and specifically Irish chapel in her will.

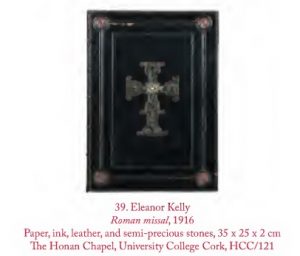

- Eleanor Kelly, who worked with the Dun Emer Press as well as taking independent commissions, bound and decorated the Roman Missal for the Honan Chapel.

-

- From Sarah Purser’s An Túr Gloine: Belfast born and trained Ethel Rhind produced the St Charthage window. Catherine O’Brien, who would take over An Túr Gloine when Pursuer retired in 1940, produced three of the windows: St. Flannan, St Munchin and St John.

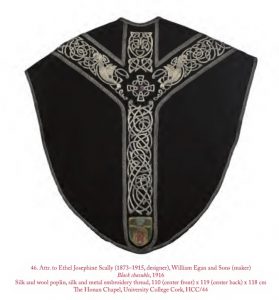

- In the textile arts, the chief contributors were William Egan and Sons in Cork and the Dun Emer Guild. Egans concentrated on vestments for the celebrants and many of the women embroiders are anonymous and their names lost to time. A few however left their names or initials on their work. This included Ethel Scally, who was actually one of the chief designers of the needlework patterns. Another is an N. Barry, who left her mark on a gold chausable and is the same Nan Barry who went on to join Cork’s branch of Cumann na mBan in 1921.

-

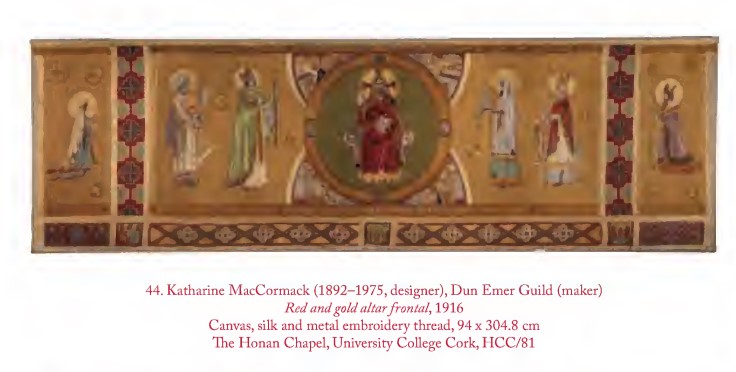

Black Cope for Honan Chapel by Ethel Scally - The Dun Emer Guild was responsible for the altar furnishings and carpets. Gleeson’s niece, Katharine (Kitty) MacCormack is credited with the design of several of the altar furnishings:

Many more women who worked on the lace and other textiles that adorn or have adorned the Chapel will remain unknown but it’s still important to acknowledge their anonymous contributions. After all, isn’t often said that “anonymous was a woman”? There are other artists whom I hope to include in later posts, including Mia Cranwill and Countess Markievicz!

If you family comes from Ireland, it’s possible that one of these lace factories or other cottage industries had a centre near your family. Maybe you have a mastercraftswoman in your family tree.

For further reading, try The Gazetteer of Irish Stained Glass by Nicola Gordon Bowe, David Caron, and Michael Wynne (Irish Academic Press, 2021) and The Arts and Crafts Movement: Making It Irish by Vera Krielkamp (ed)(University of Chicago Press, 2016)

References:

- Krielkamp, V., “Introduction”, in Krielkamp, Vera (ed.) The Arts and Crafts Movement: Making It Irish, University of Chicago Press, 2016, pp 9-26

- Hyde, D., From “The Necessity for De-Anglicising Ireland”, November 1892

- Cunningham, B., “Margaret Stokes: antiquarian scholar with an artist’s eye” 20 September 2011 , Royal Irish Academy Library Blog

- Goldbaum, H., “Howth Dolmen”. https://voicesfromthedawn.com/howth-dolmen/

- Lane, H. “Prefatory Note” in Catalogue of the Exhibition of Works by Irish Painters, Temple, A.G., Corporation of London Gallery 1904, p ix

- Krielkamp, V., “Introduction”, in Krielkamp, Vera (ed.) The Arts and Crafts Movement: Making It Irish, University of Chicago Press, 2016, p 5

- Krielkamp, p 17

- Larmour, P., “The Dún Emer Guild”, Irish Arts Review Winter 1984, p 24

- Larmour, P., “”The Art-Carving Schools in Ireland”, The GPA Irish Arts Review Yearbook, (1989/1990), pp. 151- 157,Irish Arts Review, p155

Bibliography

Bowe, Nicola Gordon,” The Irish Arts and Crafts Movement (1886-1925)”. Irish Arts Review Yearbook, (1990/1991), pp. 172-185

Cunningham, Bernadette., “Margaret Stokes: antiquarian scholar with an artist’s eye” 20 September 2018. https://www.ria.ie/news/library-library-blog/margaret-stokes-antiquarian-scholar-artists-eye

Goldbaum, H., Howth Dolmen. https://voicesfromthedawn.com/howth-dolmen/

Hyde, Douglas., From “The Necessity for De-Anglicising Ireland”, November 1892 https://www.encyclopedia.com/international/ encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/necessity-de-anglicising-ireland

Lane, Hugh. “Prefatory Note” in Catalogue of the Exhibition of Works by Irish Painters, Temple, A.G., Corporation of London Gallery 1904, p ix -xi

Krielkamp, Vera (ed). The Arts and Crafts Movement: Making it Irish, University of Chicago Press 2016, pp 9-26

Larmour, Paul. “The Art-Carving Schools in Ireland”, The GPA Irish Arts Review Yearbook, (1989/1990), pp. 151- 157, Irish Arts Review

Larmour, P., “The Dun Emer Guild”, Irish Arts Review Winter 1984, Vol 1 No 4, pp 24-28