by Hilary Kiely

The 15th of March is the anniversary of a tragic and disturbing episode from Tipperary. A young woman by the name of Bridget Cleary was burned to death by her own family on that day in 1895. Her death is sometimes spoken of as the last witch burning in Ireland. This is inaccurate. Although perhaps implied by the haunting children’s rhyme

Are you a witch? Are you a fairy?

Are you the wife of Michael Cleary?,

Bridget was not in fact suspected of practicing witchcraft. Rather, her family suspected that the woman subjected to questioning, testing, and trial by fire was not in fact Bridget (Boland) Cleary at all, but a changeling.

Folklore of stolen children

In folklore, a changeling is a fairy who has taken a person’s place. Most often tales of changelings are about young children, especially infants. A child failing to thrive or fallen ill with something not easily explained or cured was thought replaced by a wizened old fairy. An illness or a change in someone’s behaviour was sometimes explained as the person being away with the fairies or taken by fairies.

Fairies were thought to target unusually promising young children, most especially those not yet baptised. In their place, they would leave instead creatures with pinched and withered features, who spoke with hollow voices. They cried constantly and could not be consoled, ate with huge appetite but did not grow. Although infants, they were unnaturally shrewd and knowing. “In other words, the uninformed observer might think them precocious children in delicate health” (Mooney, p 141).

According to folk tales, a mother may take a long time to admit the presence of the changeling and often had to be told by some visitor to the house. Often a traveling tinker or tailor would catch the child doing something like talking, singing, dancing or even playing the bagpipes in its cradle when it thought no one would see.

Then the wise woman or fairy woman would be called in to bring back the stolen child. The method might involve heating an iron shovel in the fire, place the changeling upon it and putting it out upon the dunghill. Returning to the house, she would recite certain words, after which the family go out to the dunghill and find there the real child has been returned, while the changeling has been taken away again by the fairies. The child, though, rarely lives long after its return, owing to the rough treatment it receives while in the hands of the fairies. (Mooney, p 145)

A changeling is not always an infant, however.

Away with the Fairies

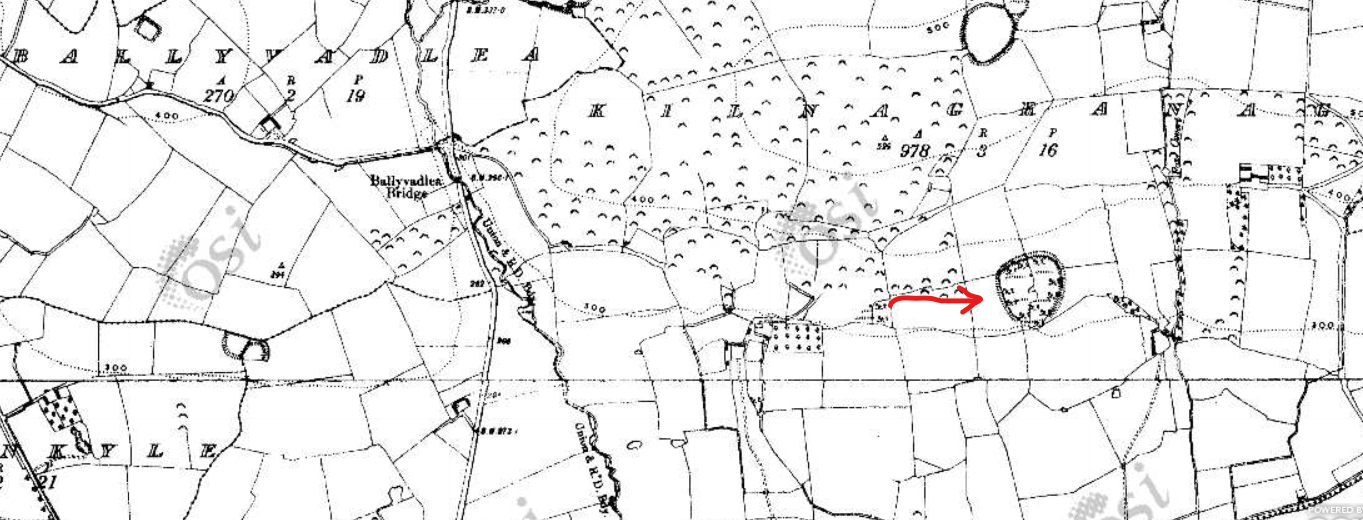

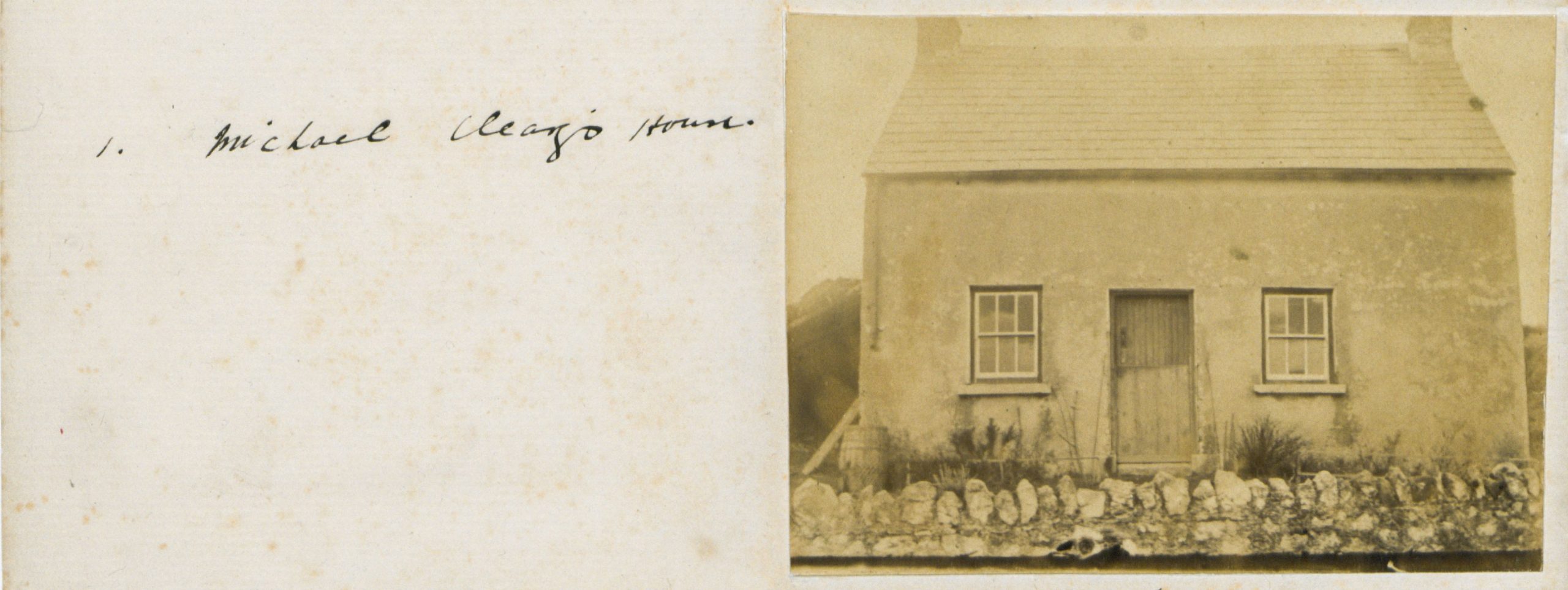

In the case of Bridget Cleary, she often passed the fairy fort on the hill at Kilnagranagh on her way to sell her eggs. One cold and snowy day, she fell ill after returning from one such trip and took to her bed with a headache and chills. The doctor was sought but after both her father and her husband had gone seeking him, it took some days before he arrived. When the doctor finally came, Bridget had not much recovered but the doctor was not terribly concerned, leaving some medicine and orders for rest. A priest also visited, declared himself unconcerned, but administered Last Rites. Just in case, apparently.

Bridget had been ill for 8 days at this point and her husband Michael was becoming convinced there was more than a chill at play here. He began to express the notion that she had been abducted at the fairy fort and a changeling had come home in her place. He went to a local herb-doctor and was given a concoction of herbs boiled in milk, which when poor Bridget did not want to drink it was prodded with a hot poker to get her to open her mouth for it.

Over the next few days she was subjected to all manner of questioning not just by her husband, but by various relations. She was forced to choke down dry bread while swearing by god she was Bridget Boland, wife of Michael Cleary. She was drenched in concoctions of urine and milk and held over the fire.

Not surprisingly, none of this helped her recover from her illness. By the 15th of March, Michael had become (apparently) convinced the woman in the house was two inches taller than Bridget and “too fine” to be his wife. She was not answering his questions, eating or drinking to his satisfaction. His conviction persuaded as many as a dozen of their friends and family that she was a changeling. Only fire would drive out the fairy and bring Bridget back. And so it was that they held her to the flames to let the fairy go up the chimney.

Bridget burned to death.

Over the next few days, after burying his wife in a shallow grave, Michael went to the fairy fort at Kilnegranagh, he said, to wait for his wife to return, claiming she had told him she would be come on a grey horse and if her cut her free from the horse she would stay with him. Had Michael actually taken this from folklore?

Caoimhin o Danachair collected this story in Limerick:

An Irish changeling story

There was a young man in this place a long time ago, and he married a nice girl and settled down. After a time she got sick and began to fade away, and she got so faded and ugly looking that she did not seem to be the same person at all. He wasn’t able to recognise her as the girl he had married. He went to see her people and they were talking of what they should do, and one of them said they should go to an old should do, and one of them said they should go to an old woman in the place who had great cures.

So the old woman came and looked at the girl, and after a while she came out to them and told them that it wasn’t his wife that was there at all, but a fairy woman, and that the fairies had taken his wife* She told them to get ready to do some harm to the person in the bed and see what would happen. So they put down a big fire, and began to heat irons in it, to burn her. When the irons were red-hot they went down into the room, and one of them had a red-hot spade in his hand and another of them with a red-hot coulter, and another with a red-hot pitchfork. When she saw them coming she let out a screech and called out that she was a fairy woman, and that she would tell where the wife was if they did not burn her. So they put the irons back in the fire and told her to tell them where the wife was and be quick about it.

” She’s in the fort,” says she, ” and she comes out every night with the fairy riders, and the only one that can save her is her husband.” The husband was so fond of her that he would do anything to save her. ” Go down to the fort to-night,” says the fairy woman, ” and be in the gap in the fort ditch at the stroke of twelve, and take a bottle of holy water, and a black-hafted knife with you, and shake the holy water in a ring on the grass.

The fairy riders will come out of the fort, and she will be riding a grey horse. Cut the reins of the horse with the knife, and pull her into the circle, and you will be safe until morning, and then you can bring her home.”

So he went to the fort and did all the things that she told him to do, and sure enough, the riders came out at the stroke of twelve. He made a slash at the reins of the grey and pulled his wife into the circle. It was then the hullabaloo commenced, for the fairies were all running and shouting and screaming all around the ring of holy water, but they could not come inside it. The shouting and screaming kept up until dawn broke, and then they all disappeared into the fort. The young man took his wife home, and they were never again troubled by the good people. (O Danachair, pp220-1)

One story could have influenced the other or both been influenced by a tale older still, as O Danachair’s collection wasn’t published until 1947.

Blacksmiths and fairies

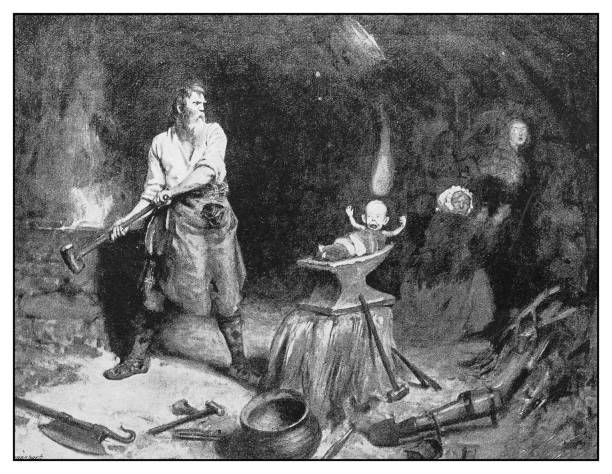

Michael Cleary was a cooper, a barrel maker, by trade. His trade would have seen him cross paths with someone who could have solved the problem of whether Bridget had been replaced by a changeling more efficiently than anyone he did call upon: a blacksmith.

The folklore around the supernatural powers of the blacksmith is ancient. The smith’s ability to transform raw ore into edged weapons or plough share became an attribution of transformative powers in other circumstances, being sought for both curses and cures, finding lost or stolen things, uncovering lies, performing marriages, and detecting changelings.

Some believed that a blacksmith could detect— and banish— a changeling. For example, in one story told in Tipperary, a smith immediately identifying a changeling, traveling with her mother, by its enormous head and spindly limbs. He then carried the “child” around the forge three times, stopping to dip it into the cooling trough each time. He sent the woman on her way with a bottle of the forge water with which to anoint the changeling for three nights in the hour before midnight, whereupon, presumably her real child would be returned to her (Thomas Fuller, Bansha, Co. Tipperary, NFC:TSC, Volume 0575, p 207- 209).

Slater’s Directory of 1856 states that there were 13 blacksmiths in Clonmel town, There was probably at least one in Ballyvadlea or near enough. Indeed, the local smith may have made the hoops that held together the barrel staves the Cleary made. Surely he would have helped to save the man’s wife.

Brewery of Eggshells

Another piece of folk wisdom has it that you can get a changeling to reveal itself with eggshells. As Bridget herself kept hens and made money for the household by selling eggs, this remedy would have been easy to hand.

One story from Mayo advises filling eggshells with water and carrying them as if they are extremely heavy (Thomas Burke, Ballyrourke, Co Mayo NFC:TSC, Volume 0103, Page 114). The changeling would be so astonished that it would laugh and exclaim something like: “For eight thousand years have I lived, and I have never yet seen anything so funny!”

Another tale from Mayo related that a widow’s child grew ill and no doctor could cure him. An old woman came by the house one day and woman said,

“the fairies have your child and if you do what I tell you, you will get your child back again. She said “put down a pot of water on the fire get a few score of eggs, break the eggs put the shells into the pot and throw the yolks back on the floor. Then the old man will sit up in the cradle and say, “what are you doing Mama” and you will answer “boiling eggshells a vick,” he will ask it three times. The third time he will ask it he add I am eighty hundred years and a boiled eggshell I never seen saw before. Then you make an effort to burn him and he will jump out of the cradle and you will get your child back.

The widow then put down a pot of water and she got a score of eggs. The first shellshe put into the pot the child sat up in the cradle this he did not did do for a long time before that. Then he said what are you doing Mama,” the widow answered “boiling eggshells a vick,” he asked it three times. The third time he he added I am eighty hundred years and a boiling eggshell I never saw till now. The woman ran to the cradle to burn the old man. He jumped out of the cradle and he was never seen again. The widows child was left back.” (Mary Barrett, Townaghmore, Co Mayo, NFC:TSCVolume 0147, Page 384)

With Bridget not selling her eggs for more than a week, the Cleary household would have had plenty of shells ready to work with.

Punishment

Michael Clearly eventually served 20 years in prison for his wife’s murder, and some of the other men involved would serve time as well. It was not a witch burning and, while it remains unknown whether Michael’s belief was sincere or a pretence to do violence to his wife, seemingly at least some of those involved sincerely believed that Bridget had been taken away with the fairies and thus it was not she that was being subjected to the torturous treatment that led to her terrible death.

Sources:

- Duchas, The Folklore Collection https://www.duchas.ie/en

- https://www.libraryireland.com/articles/Burning-Bridget-Cleary/index.php

- https://www.nationalarchives.ie/article/behind-scenes-bridget-cleary/

- Ó Danachair, Caoimhín. “Folk Tales From County Limerick”, Béaloideas , Meitheamh-Nodlaig, 1947, Iml. 17, Uimh 1/2 (Meitheamh-Nodlaig, 1947), pp. 201-225

- Mooney, James. “The Medical Mythology of Ireland”, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society , Jan. – Jun., 1887, Vol. 24, No. 125 (Jan. – Jun., 1887), pp. 136-166